Indian Holocaust My Father`s Life and Time - SIX HUNDRED TWENTY TWO

Palash Biswas

http://indianholocaustmyfatherslifeandtime.blogspot.com/

http://basantipurtimes.blogspot.com/

White Salty Dry Ocean and Intact Conch Bangles in DHOLAVIRA HARAPPAN METROPLIS Showcases Non Aryan Super Civilisation Destroyed by ARYAN Invaders!

I landed in Gandhidham, Kuchchh at 5PM on 13th April before scheduled time. Nagsi and Narang arrived shortly on the Palat farm shortly. I entered Gujarat in the Morning and first saw GODHRA, the place famous with Gujarat Genocide. Rest of Gujarat is an Amazing story of swift Urbanisation, Industrialisation and Infrastructure. Gandhidham is near Kandhla Port and Adani Power Plant is not so far.

Gandhidham is surrounded by SEZ on the land owned by Detribed KOLI and PARDHI aborigin people.

I visited SHAMAKHYALI also on the way to DHOLAVIRA.The journey between AHMEDABAD to Godhra is all about entering in the Industrilised world of Controversial Narendra Modi and his associate India Incs and MNCs.

I visited DHOLAVIRA, the Island amidst DRY SALTY White Ocean of Kuchchh RANN on 15th APRIL.

I addressed Public Meeting in Gandhidham at NIGHT on 14th APRIL as it was HOT. The atmosphere was tense as Stetue of Dr Ambedkar was broken at RAJKOT but we kept silence in the public meeting attended by no less than TEN THOUSAND SC, ST and OBC people from all parts of KUCHCHH as well as GUJARAT.

Dholavira Experience have enhanced my view of Linking the Missing Links of History. While I called back Home from the FIVE THOUSAND Years Old Metropolis Museum and informed her about the INTACT Five Thousand Years Old Conch bangles, she was EXCITED so much so that demanded to bring home the Bangles. The Conch Bangles are Mandatory for the Hindu Married woman in Eastern India Comprising Bihar, Bengal, Orissa, Assam and Tripura as well as in Bangladesh. The Idols resemble indigenous gods and goddesses. House appliances are same as found in Eastern parts of India.

The NON ARYAN Civilisation in Bengal and Eastern India is , NO DOUBT,directly LINKED with MOHANJODORA HARAPPA DHOLAVIRA LOTHAL Indus Saraswati Valley Civilisation.

-

Indus Valley Civilization - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

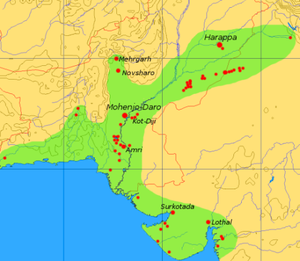

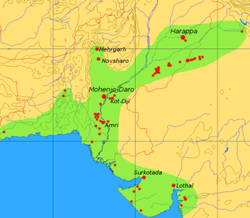

The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE) that was located in the northwestern region ...

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization - Cached - Similar -

The Harappan Civilization by Tarini J. Carr

The Harappan civilization once thrived some several thousand years ago in the Indus Valley. Located in what's now Pakistan and western India, it was the ...

www.archaeologyonline.net/.../harappa-mohenjodaro.html - Cached - Similar -

Images for harappan civilisation

- Report images -

-

Harappa Civilisation

Information about ancient indian history of Harappa Civilisation.

www.indhistory.com/harappa-civilisation.html - Cached - Similar -

Harappan civilization in India - History for Kids!

3 Mar 2011 ... By around 2000 BC, though, the Harappan civilization had collapsed. We don't know what caused this collapse. Most people think the most ...

www.historyforkids.org/learn/india/history/harappa.htm - Cached - Similar -

The Harappan Civilization

A discussion of the mathematics and a astronomy of the Harappan Civilization.

visav.phys.uvic.ca/~babul/AstroCourses/P303/harappan.html - Cached - Similar - [DOC]

HARAPPAN CIVILISATION

File Format: Microsoft Word - Quick View

19 Aug 2007 ... It has a rich collection of a large number of artifacts from the sites ofHarappan Civilisation. The collection includes pottery, seals, ...

www.indiahabitat.org/.../Galleries%20of%20National%20Museum.doc - Similar -

Harappan civilisation had three growth epi-centres

In what may eventually help unveil the mystery behind the collapse of the Indus Valleycivilisation, Indian researchers have identified three distinct ...

www.deccanherald.com › National - Cached - Similar -

Indus Valley Civilisation- Indus Valley, Harappan Civilization ...

Ancient Indus River Valley Civilization thrived from 3300-1700 BC. Its name Harappan Civilization is based on the first unearthed city of Indus Valley.

www.culturalindia.net/indian-history/.../indus-valley.html - Cached - Similar -

Timeline results for harappan civilisation

More timeline results »2500 BC The findings, if confirmed, will dislodge the Harappan Civilisation dating back to2500 BC as India's oldest civilization.

www.hinduwisdom.info1900 BC Scolars state that mature Harappan civilisation lasted from c.2600 to 1900 BCE. With the inclusion of the predecessor and. successor cultures ...

books.google.com

The Road amidst White KUCHCHH RANN from Gnadhidham to Dholavira is no less than TWO Hundred KM and it was too HOT . We started a little late and reached the Ancient Metropolis around 1.00 AM. It took only four hours. Narang Garba was driving the AC Car. But the environment seemed to be fierce SUN STORM! Vinoy SURAI, NAGSI and SARNATH Gaikawad accompnied! They knew the local people and the staff at the Museum. They guided us in hot and hosted us.

We had meetings in the villages. We also met local people in Shamakhyali!

During journey to and fro Gandhidham, I came across cross section of people. I boarded the Gandhidham Express from Howrah after Midnight Two hours late than scheduled time at 1AM with Muslim People going to Bihar. A newly married couple from TRIVENI accompanied me upto Gandhidham. The Man Palash Mitra and his bride Tapati engaged me throughout. Tapti is from RISRA across Hugli from sodepur. In Return Journey from Gandhidha, I had to get my train from Ahmedabad. I traveld by Kamakhya Express. A group of boys from Tripura and Assam joined me who work in industries situated in saurashtra and Kutchh. The Tripuar boys belong to BILUNIA near Comilah bored and I visited the area with Marxists Ministers Anil Sarkar and Badal Chowdhuri way back in 2002. At the time, I also visited the archaeological site in the area which showcases the Indigenous aboriginal Buddhist Age in India. It was Exciting.

I got Ahemedabad Howrah Express after Midnight at 1AM. In the waiting room , a bright youngman from Jalaur, Rajasthan, GAHOLAT met me with the packed Dinner. Soon , another youngman from Jamnagar joined us. I was friendly with a Bihari family residing in Saurashtra and going to Hardwar, Uttarakhand , my home state. Little ANUSHKA was quite entertaining during the waiting. I Ahamedabd Express Muslim Families from Ranaghat, Bagula and Murshidabad joined me who boarded the train from Vadodara, Surat and Bharoch. There were some Maulavies who were perfoming Namaz. They intended to use their VOTE in Bengal Elections. They enquired about Bengal situation.I explained that it would NOT make any difference to the Excluded Communities including Muslims. It was also EXCITING.

But the most exciting experience was to FEEL the warmth of the foot print of our demonised destructed Ancestors FIVE THOUSAND Years old in Dholabira. The SUN Bite and Heat Wind did not matter at all.

Dholabira is situated as an ancient and small villagelocated at a corner of island of KHADIR situated in the Great RANN of Kuchchhin Bhachau Taluka of district Kachchh, gujarat.

The ancient site known as KOTADA (large fort) spans an area of about 100 hectares nearly half of which is appropiated by the fortified settlement of the HARAPPANS!The site is surrounded by two seasonal nallahs, Mansar in the north and Manhar in the south.

As a result of the extensive excavations, which are only ten percent to this date as UNESCO fund for the proposed World heritage is waited for the incomplete task,DHOLABRA nevertheless emerged as a major HARAPPAN city remarkable for its exquisite TOWN Planning, Monumental structures, Aesthetic architecture and amazing Water mangement and storage system which are quite absent in Mdern Metros like Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and of course, KOLKATA!

I t has to be noted that DHOLABIRA has provided a long succession of Rise and Fall of FIRST INDIAN LITERAT URBAN SCIENTIFIC CIVILSATION which was the CENTRE ocf COMMERSE with rest of the world, Centarl Asia, MESOPOTAMIA and China!What the Aryans, zionist INVADERS, the ancestors of modernday foreigner Brahaminical Market dominating Class have DONE , it is quite clear with the evidence that the History and Heritage of URVBAN Ancient NON ARYAN may not be traced. But DHOLABIRA has a unique distinction of yielding an INSCRIPTIONof TEN arge signs of HARAPPAN SCRIPT, indeed the OLDEST sign Board in Human History which resembles the Chinese Japanese methodology of scripting! Moreover, a variety of funerary structures is another feature of exceeding important new light on the Socio Religious beliefsof Compsite liberal free ETHNIC groups in the Indian aborigine demography of the Harappan Metropolis, contrary to the ARYAN Monoplistic Civilisation based on ETHNIC Cleansing and GENOCIDE Cultre sustained even today with hardcore Zionist Mnusmriti Rule of the Global Order!

The identification of a Stadium with adequate seating arrangement and introduction of MIDDLE Town added a new feature to Harappan studies.The archaeological excavations at the site near LARKANA na MOHANJODORO across the Border, have revealed seven significant CULTURAL stages documenting the rise and fall of the first Indigenous URBANIZATION in the South Asian Geopolitics.

Stage one: The first settlers resided there with ADVANCED Ceramic Techniques, Copper workings, Lithic industry,bead making,stone dressingand certain principles of Planningand architecture. They constructed a formidable fortification around the Settlement. The houses were made of moulded mudbricks of standard sizes.

Stage Two: It is marked with widening of the fortification,increase of ceramic forms, decorations and in the quantity of minor antiquites.

Third stage: it is understod to be very CREATIVE period in Dholabira. The small settlement grew into a large town having Two Fortified major divisions in addition to annexes and water reservoirs, all within the peripheral wall.The exciting fortified settlement was in fact made into CITADEL and another fortified sub division was added to it in the West. These Two sub divisions had been designed and designated as CASTLE and BAILY respectively.The Brahaminical officials of the EXCAVASION deny any Aryan INVASION and try their best to Establish that the Civilisation and earlier Literate settlement had been DAMAGED by Natural calamity like Earthquake of SEVER Magnitude and consequently, large scale repairs were executed and significant changes were made in the Planing. However , it proves the SUPERIOR Technical Expertige of our ancestors. And it is said that the City was EXTENDED Eastwards.during the substage, the monumental gateways alongwith their front terraces were introduced

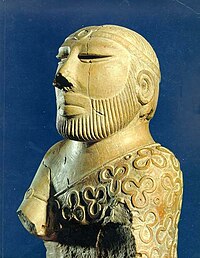

Stage Four belongs to CLASSICAL HARAPPAN Civilistion and Culture so liberal and Developed.The famous INSCRIPTION of Ten large sized signs of the Harappan script found in the North Gate should also pertain to the stage. All the Calssical harappan elemenst as Pottery,SEALs, Lithic Tools, Beads, wieghts and other items of Gold, Copper, stone , SHELL and Clay have been found which have been BRANDED as ARYAN in So Cllaed sanatan Hindu Aryan heritage denying the EXISTANCE of Indigenous Supremacy.Among most impressiveitems are elements of Functional pillars and free standing COLUMNs made of locally available Lime stones.

Stage Five is caharcterised by the generakl decline particularly in maintenace of the city as is more vividly reflected in the citadel. However , the other items such as Pottery, seals etc continued to develop.

Archaelogical experts claim that the Stage Six presents an entirely different form of the Harappan Culture that has been found widely distributed in other Parts of GUJARAT. the culture might have been undergone DRASTIC Transformation by improving and incorprating in it diverse pottery traditions coming from the sites of SIND, south Rajasthan and Gujarat while many HARAPPAN traditions ,albiet in changed formsand styles, were still sustained in Pottery, Seal satmp and wieghts.

At DHOLAVIRA, traces of late Harappan Culture is present !

Stage SEVEN depicts the ARRIVAL of New Comers who are said to be closely related to their predecessors.

The new people constructed their houses in an entirely new form which was CIRCULAR and were ESTABLISTED on the destructed site.

How came the DESTRUCTION? Who were Responsible?

The Brahamins would NEVER Disclose.

Thus, EXCAVATION are Interupted in different sites countrywid to wipe out the NON ARYAN Heritage and sustaining Bloddy INVADER Aryan Supremacy!

Search Results

-

3700 BC 3700 BC - The Sorath (present Saurashtra) region civilisation, dating back to 3700 BCE at some places, was distinct from the classical Harappan as it developed in the Indus Valley, say researchers in the field. "It maintained its separate identity in many ways,'' said ...

Show more

From Stone Pages Archaeo News: A civilisation parallel to Harappa? - Related web pages

www.stonepages.com/news/archives/001051.html -

3000 BC 3000 BC - Excavations in Kalibangan, near Ganganagar in northern Rajasthan, have unearthed terracotta pottery and jewellery that date back to around 3000 BC, conclusively dating the earliest spread of settlements in the state to that time. Some of these urban centres ...

Show more

From Rajasthan, Delhi & Agra - Related web pages

books.google.com/books?id=Zz0_zXPb68kC&pg=PA27 ... -

2600 BC 2600 BC - Origin of Civilisation Most of the western scholars held the view that Harappan civilisation was not an indigenous one.

Show more

From optional indian history ancient india

books.google.com/books?id=RSsYmi8uU-gC&pg=PA16 ... -

2500 BC 2500 BC - The findings, if confirmed, will dislodge the Harappan Civilisation dating back to2500 BC as India's oldest civilization.

From Hindu Wisdom - aryan_invasion_theory - Related web pages

www.hinduwisdom.info/aryan_invasion_theory14.htm -

2000 BC 2000 BC - Interestingly, this unit was used by Harappan civilisation settlement sites on the Indus valley in 2000 BC. The Kautilya's Arthasastra also mentions about the measurement unit of angulams and says that 12 angulams equal one vitasti while ten dhanus equal to ...

Show more

From India Journal - South Asian News for Southern California - Related web pages

www.indiajournal.com/pages/event.php?id=7796 -

1900 BC 1900 BC - Scolars state that mature Harappan civilisation lasted from c.2600 to 1900 BCE. With the inclusion of the predecessor and. successor cultures — Early Harappan and Late Harappan, respectively — the entire Indus Valley Civilisation may be taken to have ...

Show more

From Indian Cultural Heritage Perspective For Tourism - Related web pages

books.google.com/books?id=u21tp_JG9I0C&pg=PA5 ... -

1800 BC 1800 BC - Around 1800 BC, the Harappan Civilisation started declining. Most of the big cities were abandoned. In the remaining settlements, people used inferior building materials. The uniformity of weights and measures was also lost. Various causes have been cited for ...

Show more

From Longman History & Civics ICSE 9 - Related web pages

books.google.com/books?id=EXPouL4BYTMC&pg=PA25 ... -

1700 BC 1700 BC - By combining the results of these craft studies with similar information on subsistence, we are now beginning to better understand Harappan civilisation. The occupation of the site continued in the post-urban period up to 1700 BC. In the last phase there are ...

Show more

From Antiquity: Project Gallery - Related web pages

www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/bhan304/ -

1500 BC 1500 BC - When the ancient Indian Harappan sites (of the Indus Valley civilisation) were discovered, it was clear that these reflected a much older civilisation than could be attributed to the supposed coming of the Vedic Aryans in 1500 BCE. At this point, the Aryan ...

Show more

From MoreArticles1 - Related web pages

www.salagram.net/VWH-MoreArticles1.html -

700 BC 700 BC - The citadel may be a part of Harappan civilisation, possibly serving as a link between contemporary South Asian and Roman civilisations. The Harappan civilisationflourished in the Indus and Ganges valleys between 2700 BC and 700 BC. In Wari and the ...

Show more

From loving-bengal.net - Related web pages

www.sos-arsenic.net/lovingbengal/culture.html

Science And Technology In Harappan Culture

The Harappan people achieved great accuracy in measuring length, mass and time. The people of Indus valley civilization were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures. Their smallest division which is marked on an ivory scale found in Lothal was approximately 1.704mm the smallest division ever recorded on a scale of the Bronze Age.

Harappan followed the decimal division of measurement for all practical purposes including the measurement of mass as revealed by their hexahedron weights. These brick weights were in a perfect ration of 4:2:1 with weights of 0.05,0.1,0.2,0.5,1,2,5,10,20,50,100,200 and 500 units with each unit weighing approx 28 grams and smaller objects were weighed in similar ratios with the units of 0.871.Unique Harappan inventions include an instrumentwhich was used to measure whole sections of the horizon and the tidal dock.They also evolved new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper,bronze,lead and tin.the engineering skills of Harappans was remarkable especially in building docks after a careful study of tides,waves and currents. A touchstone bearing gold streaks was found in Banawali which was probably used for testing the purity of gold.

http://www.zahie.com/categories/details/history/science-and-technology-in-harappan-culture.html

-

Religion, Science & Astronomy of Harappa Civilization

Religion, Science & Astronomy of Harappa Civilization. ... However Historian John Keays in his book on Religion of Harappans countered this view. ...

reference.indianetzone.com/.../religion,_science_astronomy.htm - Cached - Similar -

Religion in Indus Valley Civilization

2 Nov 2010 ... Religion in Indus Valley Civilization - Informative ...

www.indianetzone.com › ... › Indus Valley Civilization - Cached - Similar -

Hinduism (religion) :: Religion in the Indus valley civilization ...

Hinduism (religion), Religion in the Indus valley civilization, Britannica Online Encyclopedia, The Harappa culture, located in what is now Pakistan, ...

www.britannica.com/.../Religion-in-the-Indus-valley-civilization - Cached - Similar -

Images for religion of harappan civilization

- Report images -

Indus Valley Civilization Religion, Religion Of Indus Valley ...

Religion Of Indus Valley Civilization, Notes On Indus Valley Civilization Religion.

www.historytution.com/indus...civilization/religion.html - Cached - Similar -

The Harappan Civilization by Tarini J. Carr

- 10:18amThe Harappan civilization once thrived some several thousand years ago in the ... and imposed their own culture and religion on them, as the theory goes, ...

www.archaeologyonline.net/.../harappa-mohenjodaro.html - Cached - Similar -

Harappa Civilisation

Harappa Civilisation - Religion. The culture and religion of the IVC overlap and perhaps repetitive symbols such as the pipal leaf and swastika have ...

www.indhistory.com/harappa-civilisation.html - Cached - Similar -

Indus Valley Civilisation- Indus Valley, Harappan Civilization ...

Religion The large number of figurines found in the Indus Valley Civilization suggests that the Harappan people worshipped a Mother Goddess, who symbolized ...

www.culturalindia.net/indian-history/.../indus-valley.html - Cached - Similar -

History - The Indus Valley Civilisation

Mohenjodaro and Harappa are now in Pakistan and the principal sites in ... Society andReligion The Harappan society was probably divided according Goddess ...

sympweb.tripod.com/IndusValleyhistory.htm - Cached - Similar -

History of Hinduism - ReligionFacts

17 Mar 2004 ... Knowledge of this great civilization's religion must therefore be based ...Period to the decline of the Indus civilization » Post-Harappan ...

www.religionfacts.com/hinduism/history.htm - Cached - Similar

| ||||||

| ||||||

| |

Dholavira

Dholavira, an ancient city, and locally known as Kotada Timba Prachin Mahanagar Dholavira, is one of the largest and most prominent archaeological sites in India, belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization. It is located on the Khadir bet island in the Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary, Great Rann of Kutch, Kachchh district of Gujarat, India. The site is surrounded by water in the monsoon season.[1] The site was occupied from c.2650 BCE, declining slowly after about 2100 BCE. It was briefly abandoned and reoccupied until c.1450 BCE.[2] The site was discovered in 1967-8 by J.P. Joshi and is the fifth largest Harappan site in the Indian subcontinent, and has been under excavation almost continuously since 1990 by the Archaeological Survey of India. Eight large urban centers have been discovered: Harappa, Mohenjo Daro, Ganeriwala, Rakhigarhi, Kalibangan, Rupar, Dholavira, and Lothal.

Contents[hide] |

Chronology of Dholavira

R.S. Bisht, the director of the Dholavira excavations, has defined following seven stages of occupation, at the site[3]:

| Stages | Dates | |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 2650-2550 BCE | Early Harappan - Mature Harappan Transition A |

| Stage II | 2550-2500 BCE | Early Harappan - Mature Harappan Transition B |

| Stage III | 2500-2200 BCE | Mature Harappan A |

| Stage IV | 2200-2000 BCE | Mature Harappan B |

| Stage V | 2000-1900 BCE | Mature Harappan C |

| 1900-1850 BCE | Period of desertion | |

| Stage VI | 1850-1750 BCE | Posturban Harappan A |

| 1750-1650 BCE | Period of desertion | |

| Stage VII | 1650-1450 BCE | Posturban Harappan B |

Excavations

The ancient site at Dholavira, is flanked by two storm water channels; the Mansar in the north, and the Manhar in the south. Excavation was initiated in 1989 by the Archaeological Survey of India under the direction of R. S. Bisht. The excavation brought to light the sophisticated urban planning and architecture, and unearthed large numbers of antiquities such as seals, beads, animal bones, gold, silver, terracotta ornaments and vessels linked to Mesopotamia. Archaeologists believe that Dholavira was an important centre of trade between settlements in south Gujarat, Sindh and Punjab and Western Asia.[4]

Architecture and material culture

Estimated to be older than the port-city of Lothal, the city of Dholavira has a rectangular shape and organization, and is spread over 100 hectares. The area measures 771.10 metres in length, and 616.85 metres in width. Like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, the city is composed to a pre-existing geometrical plan, of three divisions - the citadel, the middle town and the lower town. The acropolis and the middle town had been further furnished with their own defence-work, gateways, built-up areas, street system, wells and large open spaces. The acropolis is the most carefully guarded as well as impressive and imposing complex in the city of which it appropriates the major portion of the southwestern zone. The towering "castle" stands majestically in fair insulation and defended by double ramparts. Next to this stands a place called 'bailey' where important officials lived. The city within the general fortification accounts for 48 hectares. There are extensive structure-bearing areas though outside yet intimately integral to the fortified settlement. Beyond the walls, yet another settlement has been found. The most striking feature of the city is that all of its buildings, at least in their present state of preservation, are built out of stone, whereas most other Harappan sites, including Harappa itself and Mohenjo-daro, are almost exclusively built out of brick.[5]

Reservoirs

One of the unique features of Dholavira is the sophisticated water conservation system of channels and reservoirs, the earliest found anywhere in the world and completely built out of stone, of which three are exposed. They were used for storing the fresh water brought by rains or to store the water diverted from a nearby rivulet. This probably came in wake of the desert climate and conditions of Kutch, where several years may pass without rainfall.

The inhabitants of Dholavira created sixteen or more reservoirs of varying size during Stage III. Some of these took advantage of the slope of the ground within the large settlement, a drop of 13 m from northeast to northwest. Other reservoirs were excavated, some into living rock. Recent work has revealed two large reservoirs, one to the east of the castle and one to its south, near the Annexe.[6]

Reservoirs are cut through stones vertically. They are about 7 meters deep and 79 meters long. Reservoirs skirted the city while citadel and bath are centrally located on raised ground.[7] A large well with a stone-cut trough to connect the drain meant for conducting water to a storage tank also found.[7] Bathing tank had steps descending inwards.

Other structures and objects

A huge circular structure, believed to be grave or memorial is found. However no skeleton or human remains found under structure. The circular structure is built with ten radial walls of mud bricks in a shape of spoked wheel.[7] A soft sandstone sculpture of a male with phalluserectus but head and feet below ankle truncated was found in the passage way of the eastern gate.[7] Also many funerary structures were found, however except one they were devoid of skeletons. Also many pottery pieces, terracotta seals, bangles, rings, beads and intaglio engraving found.

Language and Script

It is not known which language the Harappan people spoke, and their script cannot be read. It had about 400 basic signs, with many variations. The signs may have stood both for words and for syllables. The direction of the writing was generally from right to left. Most of the inscriptions are found on seals (mostly made out of stone) and sealings (pieces of clay on which the seal was pressed down to leave its impression). Some inscriptions are also found on copper tablets, bronze implements, and small objects made of terracotta, stone andfaience. The seals may have been used in trade and also for official administrative work. A lot of inscribed material was found at Mohenjo-daro.

Sign board

One of the most significant discoveries at Dholavira was made in one of the side rooms of the northern gateway of the city. The Harappans had arranged and set pieces of the mineral gypsum to form ten large letters on a big wooden board. At some point, the board fell flat on its face. The wood decayed, but the arrangement of the letters survived. The letters of the signboard are comparable to large bricks that were used in nearby wall. Each sign is about 37 cm high and the board on which letters were inscribed was about 3 meter long.[8]

How to reach Dholavira

Dholavira is located in the Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary in the Great Rann of Kutch.

- By Air

- The nearest airport is in Gandhidham about 250 km away, where a daily flight between Mumbai and Gandhidham is available. Another airport close to Dholavira is Bhuj Airport about 300 km away, where daily two flights between Bhuj and Mumbai are available.

- By Rail

- Samakhyali (160 km) on the Palanpur-Gandhidham BG line.

- By Road

References

- ^ http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1090/

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/160814/Dholavira

- ^ Possehl, Gregory. (2004). The Indus Civilization: A contemporary perspective, New Delhi: Vistaar Publications, ISBN 81-7829-291-2, p.67.

- ^ http://www.archaeology.org/0011/newsbriefs/aqua.html

- ^ http://accidentalblogger.typepad.com/accidental_blogger/2008/08/water-managemen.html

- ^ Possehl, Gregory. (2004). The Indus Civilization: A contemporary perspective, New Delhi: Vistaar Publications, ISBN 81-7829-291-2, p.69.

- ^ a b c d United News of India (1997-06-25). "Dholavira excavations throw light on Harappan civilisation". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 2008-09-30. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory. (2004). The Indus Civilization: A contemporary perspective, New Delhi: Vistaar Publications, ISBN 81-7829-291-2, p.70.

External links

- Excavations at Dholavira in Archaeological Survey of India website.

- Computer graphics reconstruction of Dholavira

- The Old World - Dholavira

- Dholavira (Gujarat, India)

- Dholavira excavations throw light on Harappan civilisation, United News of India 1997

- Nisid Hajari, "India's Salt Lake Cities", in Time Magazine 1 September 1997

- World Heritage Site, All Tentative Sites, Here is an overview of all Tentative list, last updated June, 2006.

- World Heritage, Tentative Lists, State : India.

- Dholavira: a Harappan City, Gujarat, Disstt, Kachchh - UNESCO World

- Jurassic Park: Forest officials stumble upon priceless discovery near Dholavira; Express news service; Jan 08, 2007; Indian Express Newspaper. Also see [1], [2]

- Trip Record: Photos of Friends on a motorbike trip through Kutch visiting the Great Rann of Kutch passing through Kala Dungar (Black hill), snow white Rann, then they visit the Dholavira Harappan excavation site. Then biking through Banni grasslands they see Indian Wild Ass there and Chari-Dhand Wetland Conservation Reserve. They then Bike to Lakhpat fort village and also Mandvi beach.. Also see[3].

- ASI's effort to put Dholavira on World Heritage map hits roadblock; by hitarthpandya; Feb 13, 2009; Indian Express Newspaper

- ASI to take up excavation in Kutch's Khirasara; by Prashant Rupera, TNN; 2 November 2009; Times of india

-

Dholavira Maps - Tourist, Tourism map of Dholavira

Explore tourism map of Dholavira. Road map of Dholavira city and surrounding destinations.... Dholavira. Kutch. Kandla. Bhuj. Gandhidham. Morvi. Wankaner ...

www.holidayiq.com › India › Gujarat - Cached -

Dholavira Ruins, Kutch, Dholavira Ruins in Kutch

indianholiday.com offers online information on Dholavira Ruins, Kutch, Dholavira Ruins ...Kutch Dholavira Ruins carry some of the very elegant and precious ...

www.indianholiday.com/.../dholavira-ruins-kutch.html - United States - Cached - Similar -

Images for dholavira kutch

- Report images -

Kutch India Tour - Dholavira

Khadir Island tour: Dholavira (Kutch Tours) - tour #2115, Khadir Island private tour, Khadir Island private guide.

www.toursbylocals.com/DholaviraHarrapanTourGiude - Similar -

Dholavira: Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary, Dholavira Tourist ...

Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary - Dholavira places.

www.mustseeindia.com/Dholavira-Kutch-Desert-Wildlife.../18623 - Cached -

Dholavira, Indus Valley Civilization, Lothal - KutchForever.com

Above all the Harappan sites, the site of Dholavira nearby known as Kotada, in the Khadir island of Kutch stands separately. ...

www.kutchforever.com/Dholavira.aspx -Great Rann of Kutch

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaThe Great Rann of Kutch[1] also called Greater Rann of Kutch[2] or just Rann of Kutch (Gujarati: કચ્છનું મોટું રણ), is a seasonal salt marsh located in the Thar Desertin the Kutch District of Gujarat, India and the Sindh province of Pakistan.

The name "Rann" comes from the Hindi word ran (रण) meaning "salt marsh". The Hindi word is derived from Sanskrit/Vedic word iriṇa (इरिण) attested in the Rigvedaand Mahābhārata.

Contents

[hide][edit]Location and description

The Great Rann of Kutch, along with the Little Rann of Kutch and the Banni grasslands on its southern edge, is situated in the district of Kutch and comprises some 30,000 square kilometres (10,000 sq mi) between the Gulf of Kutch and the mouth of the Indus River in southern Pakistan. The marsh can be accessed from the village of Kharaghoda in Surendranagar District.

In India's summer monsoon, the flat desert of salty clay and mudflats, averaging 15 meters above sea level, fills with standing waters, interspersed with sandy islets of thorny scrub, breeding grounds for some of the largest flocks of Greater and Lesser Flamingoes, and is a wildlife sanctuary [7]. At its greatest extent, the Gulf of Kutch on the west and the Gulf of Cambay on the east are both united during the monsoon.

During the flooding wildlife including the Indian Wild Ass shelters on islands of higher ground called bets.

The area was a vast shallows of the Arabian Sea until continuing geological uplift closed off the connection with the sea, creating a vast lake that was still navigable during the time of Alexander the Great. The Ghaggar River, which presently empties into the desert of northern Rajasthan, formerly emptied into the Rann of Kutch, but the lower reaches of the river dried up as its upstream tributaries were captured by the Indus and Ganges thousands of years ago. Traces of the delta and its distributary channels on the northern boundary of the Rann of Kutch were documented by the Geological Survey of India in 2000.

The Luni River, which originates in Rajasthan, drains into the desert in the northeast corner of the Rann and other rivers fedding into the marsh include the Rupen from the east and the West Banas River from the northeast.

This is one of the hottest areas of India.

[edit]Flora

The plant life of the marsh consists of grasses such as Apluda and Cenchrus species along with dry thorny shrubs.

[edit]Wildlife

The Rann of Kutch is the only place[citation needed] in Pakistan and India where flamingoes come to breed. There are 13 species of lark in the Rann of Kutch. The Little Rann of Kutch is famous for the Indian Wild Ass sanctuary, where the worlds last population of Indian Wild Ass (Equus hemionus khur or khar) still exists. Other mammals of the area include the Indian Wolf (Canis indica), Desert Fox (Vulpes vulpes pusilla), Golden Jackal (Canis aureus), Chinkara (Gazella bennettii), Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus), and the threatened Blackbuck(Antilope cervicapra).

The marshes are also a resting site for migratory birds, and are home to over 200 species of bird including the threatened Lesser Florican(Eupodotis indica) and Houbara Bustard (Chlamydotis undulata).

[edit]Threats and preservation

Although most of the marsh is in protected areas the habitats are vulnerable to cattle grazing, firewood collection and salt extraction operations, all of which may involve driving road vehicles and this disturbing wildlife. There are several wildlife sanctuaries and protected reserves on the Indian side in the Rann of Kutch region. From the city of Bhuj various ecologically rich and wildlife conservation areas of the Kutch/Kachchh district can be visited such as Indian Wild Ass Sanctuary, Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary, Narayan Sarovar Sanctuary,Kutch Bustard Sanctuary, Banni Grasslands Reserve and Chari-Dhand Wetland Conservation Reserve, etc.

On the Pakistani side in the Sindh province the Pakistani Government has created the Rann of Kutch Wildlife Sanctuary.

[edit]Indo-Pakistan international border

In India the northern boundary of the Greater Rann of Kutch forms the International Border between India and Pakistan, it is heavily patrolled by Border Security Force (BSF) and Indian Army conducts exercises here to acclimatize its troops to this harsh terrain.[1][2]

This inhospitable salty lowland, rich in natural gas is part of India and Pakistan's ongoing border dispute concerning Kori Creek. In April 1965, a dispute there contributed to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, when fighting broke out between India and Pakistan. Later the same year,Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Harold Wilson successfully persuaded both countries to end hostilities and set up a tribunal to resolve the dispute. A verdict was reached in 1968 which saw Pakistan getting 10% of its claim of 9,100 square kilometres (3,500 sq mi). The majority of the area thus remained with India. Tensions spurted again in 1999 during the Atlantique Incident.

[edit]Chir Batti

In dark nights an unexplained strange dancing light phenomena known locally as Chir Batti (ghost lights) is known to occur here in the Rann[3] and in the adjoining Banni grasslands and its seasonal marshy wetlands.[4]

[edit]In popular culture

J. P. Dutta's Bollywood film Refugee is shot on location in the Great Rann of Kutch and other locations in the Kutch district of Gujarat, India. This film is attributed to have been inspired by the famous story by Keki N. Daruwalla based around the Great Rann of Kutch titled "Love Across the Salt Desert"[5] which is also included as one of the short stories in the School Standard XII syllabus English text book of NCERTin India.[6] The film crew having traveled from Mumbai was based at the city of Bhuj and majority of the film shooting took place in various locations around in the Kutch District of the Indian state of Gujarat including the Great Rann of Kutch (also on BSF controlled "snow white" Rann within), Villages and Border Security Force (BSF) Posts in Banni grasslands and the Rann, Tera fort village, Lakhpat fort village, Khera fort village, a village in southern Kutch, some ancient temples of Kutch and with parts and a song filmed on set in Mumbai's Kamalistan Studio.

[edit]See also

- Little Rann of Kutch

- Kutch

- Kori Creek

- Atlantique Incident

- Banni grasslands

- Chhir Batti (Ghost lights) from Banni grasslands, its seasonal wetlands and the adjoining Rann of Kutch

- Chari-Dhand Wetland Conservation Reserve adjacent to Banni Grasslands

- Salt marsh

- Salt flat

[edit]References

- ^ a b Fighting for the Great Rann - It's a desolate, barren tract of land, but the armed forces guard it with a fierceness that inspires nothing short of awe. By Gaurav Raghuvanshi; Feb 25, 2005; Business Line; Financial Daily from THE HINDU group of publications

- ^ a b Far from the focus - Villages along the India-Pakistan border face official neglect and inadequate assistance. By PRAVEEN SWAMI in Bhuj; Volume 18 - Issue 04, Feb. 17 - Mar. 02, 2001; Frontline Magazine; India's National Magazine from the publishers of THE HINDU

- ^ Stark beauty (Rann of Kutch); Bharati Motwani; September 23, 2008; India Today Magazine, Cached: Page 2 of 3 page article with these search terms highlighted: cheer batti ghost lights rann kutch [1], Cached: Complete View - 3 page article seen as a single page [2]

- ^ Ghost lights that dance on Banni grasslands when it's very dark; by D V Maheshwari; August 28, 2007; The Indian Express Newspaper

- ^ Love Across the Salt Desert; by Keki N. Daruwalla. Pdf of full story posted at Boston University at [3]. Bollywood connection - J. P. Dutta's "Refugee" is said to be inspired by this story; learnhub, University of Dundee

- ^ (iii) Supplementary Reader; Selected Pieces of General English for Class XII; English General - Class XII; Curriculum and Syllabus for Classes XI & XII; NCERT. Also posted at [4] / [5], [6]

Encyclopædia Britannica

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911).Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911).Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.- The Great Run of Kutch; Dec 10, 2006; The Indian Express Newspaper

- Rann of Kutch seasonal salt marsh (IM0901); Ecoregion Profile, Flooded Grasslands and Savannas; World Wildlife Fund Report; This text was originally published in the book Terrestrial ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a conservation assessment from Island Press. This assessment offers an in-depth analysis of the biodiversity and conservation status of the Indo-Pacific's ecoregions. Also see: Rann of Kutch seasonal salt marsh (IM0901); Flooded Grasslands and Savannas; WildWorld; All text by World Wildlife Fund © 2001; National Geographic Society

[edit]External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Rann of Kutch - Rann of Kutch Festival Astrology

- World Wildlife Fund: Terrestrial Ecoregions: Rann of Kutch

- Satellite views comparing summer and winter conditions in the Rann of Kutch

- Little Rann of Kutch National Park

- Kachchh Portal a web portal about Kachchh and the people who hail from there - the global community of Kachchhis / Kutchis.

- Worldwildlife.org website

- Desert (Rann of Kutch) wetlands; 06 February 2003; WWF Global website

- KACHCHH PENINSULA AND THE GREAT RANN; The Geological Survey of India, Ministry of Mines, Government of India

- Archived News Articles from India Environmental Portal on: Rann of Kutch

- Archived News Articles from India Environmental Portal for a Search made for: Banni grasslands

- Trip Record: Photos of Friends on a motorbike trip through Kutch visiting the Great Rann of Kutch passing through Kala Dungar (Black hill), snow white Rann, then they visit the Dholavira Harappan excavation site. Then biking through Banni grasslands they see Indian Wild Ass there and Chari-Dhand Wetland Conservation Reserve. They then Bike to Lakhpat fort village and also Mandvi beach.. Also see[8].

[show]Geography of South Asia [show]Protected areas of Pakistan

SATURDAY, JANUARY 8, 2011

DHOLAVIRA-A HARAPPAN METRO

A journey to Dholavira:a Harappan metropolis

| |

DHOLAVIRA |

| |

DHOLAVIRA |

| * |

DHOLAVIRA WRITING |

| * |

STREET |

The road to dholavira goes through a dazzling white landscape of salty mudflats. It is close to noon in early April and the mercury is already past 100F. The desert monotones are interrupted only by the striking attire worn by the women of the nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoral tribes that still inhabit this land: Ahir, Rabari, Jat, Meghwal, and others. When I ask the driver of my hired car to stop for a photo, they receive me with curious stares, hoots, and giggles.The Rann of Kutch, an area about the size of Kuwait, almost entirely within Gujarat and along the border with Pakistan. Once an extension of the Arabian Sea, the Rann ("salt marsh") has been closed off by centuries of silting. During the monsoons, parts of the Rann fill up with seasonal brackish water, enough for many locals to even harvest shrimp in it. Some abandon their boats on the drying mudflats, presenting a surreal scene for the dry season visitor. Heat mirages abound. Settlement is limited to a few "island" plateaus, one of which, Khadir, hosts the remains of the ancient city of Dholavira, discovered in 1967 and excavated only since 1989.Entering Khadir, we pass a village and find the only tourist bungalow in town. It hasn't seen a visitor in three days; I check in and head over to the ruins. I've planned this for months; even the hottest hour of the day cannot temper my excitement for the ruins of this 5,000 year-old metropolis of the Indus Valley Civilization. While hundreds of sites have been identified in Gujarat alone, this is among the five biggest known to us in the entire subcontinent, alongside Harappa, Mohanjo-daro, and Ganeriwala in Pakistan, and Rakhigarhi in India.At the site office, a caretaker and his friend are playing cards on a charpoy. They offer me a chair and a glass of water, cooled in an earthen surahi. On a wall are the mysterious inscriptions from the famous signboard of Dholavira, painted above contemporary motifs to suggest a continuity of sorts. I learn from the caretaker that the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) still excavates each winter, alongside researchers from overseas. Hundreds from the local village are then employed on site. He says he has learned directly from the experts and offers to be my guide. I readily agree but hope that as part of the deal, he will overlook the "Photography Prohibited" injunction I had noticed earlier—a perfectly exasperating habit of the ASI—else I would have to attempt a bribe. I am relieved when the caretaker does not press the issue.***To the casual visitor, the most striking feature of Dholavira is its water management system. One gets the sense that every drop of water had to be saved. About 25 of the city's 250 acres are occupied by 16 rock cut reservoirs of various sizes. Linked by channels and dams, the reservoirs are quite spread out and must have added to the aesthetic appeal of this planned city. I wondered how much of the city's energy went into this effort? What drew its citizens to this location in the first place?Archaeologists have identified seven cultural stages in the city's evolution, starting around 3000 BCE. The "golden age" was apparently the fourth stage, when most of its monumental structures—gateways, fortifications, reservoirs—were built, accompanied by a prolific output in pottery, seals with inscriptions, weights, beads, and items of gold, silver, copper, ivory, shell, faience, steatite, clay, and stone. Later stages saw rising levels of impoverishment and urban decay (and a brief revival), until it was finally abandoned around 1500 BCE. We can't be sure why. But Dholavira did outlast other major centers of the Indus Valley Civilization.The city was enclosed by an outer wall. Three major sections of the city have been identified: the "citadel", "middle town", and "lower town", in descending order of prosperity and civic amenities. To the south on higher ground stands the citadel, where the "royalty" had lived. Further north is the middle town and a lower town to its east, both residential quarters for commoners, with streets and homes laid out on a grid-like plan. The caretaker points out portable wastewater pots (sullage jars) outside many houses, similar to the large earthenmatkas of today. Pottery shards lie scattered on the ground. I pick up a broken stone bangle. Someone probably wore this 4000 years ago!The imposing citadel, fortified with layers of walls, gates, and towers, has a "castle" atop with concealed passageways, stairs, and chambers, many supported by chiseled pillars of finely polished limestone. What dramas unfolded within these walls? What fears and hopes were expressed here? Or myths, anxieties, humor, repressions, prejudices? Unless the Harappan "script" is deciphered, much of what we say is speculation. What we can be sure of is Dholavira's water harvesting acumen, plainly evident in the citadel's intricate network of storm water drains, with slopes, steps, cascades, manholes, paved flooring and capstones. A tall man could walk through the large arterial drains that fed a reservoir on the citadel. The caretaker leads me to a deep well, once fitted with ropes and buckets. Water drawn from it cascaded down rock-cut channels to feed showers in a royal bathroom. Who were the people who occupied this privileged spot? What social organization supported them?Between the citadel and middle town is an open field, with stepped stands on all four sides. It might have hosted a market, royal or religious ceremonies, sports, executions, performances, or festivals. Though there is no evidence of competitive sports, some Indian historians prefer to believe so and have accordingly dubbed the field a "stadium". Overlooking this field was the citadel's north gate with the famous three-meter wide signboard of ten mysterious symbols, which must have been legible from across the field. For all we know, it might say: Long Live the King or Conserve Water!With the region's water resources clearly not ideal for agriculture, what economic activity drove the city's fortunes? Scholars have suggested that Dholavira, with its coastal location may have been a regional hub of maritime trade and commerce (back then the Rann was a navigable channel to the Arabian sea). To the modern visitor, Dholavira could well be a symbol of an epic struggle against the elements, where a whole city strived to wrestle an order out of its hostile environment. All that for what? The stones aren't talking just yet. |

Posted by hssthistory2010@gmail.com at 6:40 AM

-

Harappa - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The ancient city of Harappa was greatly destroyed under the British Raj, when bricks from the ruins were used as track ballast in the making of the ...

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa - Cached - Similar -

Images for harappan cities

- Report images -

Harappan civilization in India - History for Kids!

3 Mar 2011 ... There were two main cities that we know of, Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, about 400 kilometers (250 miles) away. Both are in modern Pakistan. ...

www.historyforkids.org/learn/india/history/harappa.htm - Cached - Similar -

The Harappan Civilization by Tarini J. Carr

- 10:18amThe Harappan civilization once thrived some several thousand years ago in the Indus Valley. Located in what's now Pakistan and western India, it was the ...

www.archaeologyonline.net/.../harappa-mohenjodaro.html - Cached - Similar -

Harappa

"Harappa was a `city' site; but the Sarasvati and Sindhu rivers had nurtured a large number of `village' sites. The state of archaeological knowledge has ...

ancienthistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa041498.htm - Cached - Similar -

Harappa Civilization

Mohenjo and Harappa were the planned cities. They were the two biggest cities, 600 km apart. They had similar planning, layout and technique in construction ...

www.indiaandindians.com/india.../harappan_civilization.php - Cached - Similar -

The Harappan Civilization

A discussion of the mathematics and a astronomy of the Harappan Civilization.

visav.phys.uvic.ca/~babul/AstroCourses/P303/harappan.html - Cached - Similar -

Mohenjo-daro the Ancient Indus Valley City in Photographs

Ancient Indus Valley city of Mohenjo-daro in 103 Slides by Dr. Jonathan Mark Kenoyer. ...Harappa.com does not support or condone the sale of antiquities. ...

www.mohenjodaro.net/ - Cached - Similar -

Harappa Civilisation

Information about ancient indian history of Harappa Civilisation.

www.indhistory.com/harappa-civilisation.html - Cached - Similar -

Town Planning of Harappa Civilization

The twin cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa were center of all activities. Both cities were a mile square, with defensive outer walls. ...

reference.indianetzone.com/1/town_planning.htm - Cached - Similar -

Timeline results for harappan cities

More timeline results »2600 BC 2600 BC Mature Harappan phase of the Indus Valley Civilization begins. The citiesof Harappa, Lothal, Kalibangan and Mohenjo-daro become large ...

botanyias.blogspot.com1900 BC Named after its city of Harappa, the civilization flourished from 2600 to 1900 BCE, developing a technologically advanced urban culture that was ...

www.thefreedictionary.com

Kutch District

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.(June 2010) |

| | This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. The talk page may contain suggestions. (March 2009) |

| Kachchh district કચ્છ જિલ્લો | |

|---|---|

Location of Kachchh district in Gujarat | |

| State | Gujarat, |

| Headquarters | Bhuj |

| Area | 45,612 km2 (17,611 sq mi) |

| Population | 1,526,321 (2001) |

| Population density | 33 /km2 (85.5/sq mi) |

| Sex ratio | 951 |

| Lok Sabha Constituencies | Kachchh |

| Assembly Seats | 6 |

| Major highways | 1 |

Kutch district (also spelled as Kachchh) (Gujarati: કચ્છ જિલ્લો, Sindhi: ڪڇ ضلو) isdistrict of Gujarat state in western India. Covering an area of 45,612 km², it is the largest district of India.

Kachchh literally means something which intermittently becomes wet and dry; a large part of this district is known as Rann of Kachchh which is shallow wetlandwhich submerges in water during the rainy season and becomes dry during other seasons. The same word is also used in the languages of Sanskrit origin for a tortoise and garments to be worn while having a bath. The Rann is famous for its marshy salt flats which become snow white after the shallow water dries up each season before the monsoon rains.

The district is also famous for ecologically important Banni grasslands with their seasonal marshy wetlands which form the outer belt of the Rann of Kutch.

Kachchh District is surrounded by the Gulf of Kachchh and the Arabian Sea in south and west, while northern and eastern parts are surrounded by the Great and Small Rann (seasonal wetlands) of Kachchh. When there were not many dams built on its rivers, the Rann of Kachchh remained wetlands for a large part of the year. Even today, the region remains wet for a significant part of year. The district had a population of 1,583,225 of which 30% were urban as of 2001.[1] Motor vehicles registered in Kutch district have their registration Number starting with GJ-12.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Geography

The Kachchh district, with 45,652 km², is one of the largest districts(Ladakh is the largest) in India. The administrative headquarters is in Bhujwhich is geographically in the center of district. Other main towns are Gandhidham, Rapar, Nakhatrana, Anjar, Mandvi, Madhapar andMundra. The district has 966 villages.

Kachchh is virtually an island, as it is surrounded by the Arabian Sea in the west; the Gulf of Kachchh in south and southeast and Rann of Kachchh in north and northeast. The border with Pakistan lies along the northern edge of the Rann of Kachchh, of the disputed Kori Creek. The Kachchh peninsula is an example of active fold and thrust tectonism. In Central Kachchh there are four major east-west hill ranges characterized by fault propagation folds with steeply dipping northern limbs and gently dipping southern limbs. From the gradual increasing dimension of the linear chain of hillocks towards the west along the Kachchh mainland fault and the epicentre of the earthquake of 2001 lying at the eastern extreme of Kachchh mainland fault, it is suggested that the eastern part of the Kachchh mainland fault is progressively emerging upward. It can be suggested from the absence of distinct surface rupture both during the 1956 Anjar earthquake and 2001 Bhuj earthquake, that movements have taken place along a blind thrust. Villages situated on the blind thrust in the eastern part of the Kachchh mainland hill range (viz. Jawaharnagar, Khirsara, Devisar, Amarsar and Bandhdi) were completely erased during the 2001 earthquake.[2]

[edit]Wildlife Sanctuaries and Reserves of Kutch

From the city of Bhuj various ecologically rich and wildlife conservation areas of the Kutch / Kachchh district can be visited such as Indian Wild Ass Sanctuary, Kutch Desert Wildlife Sanctuary, Narayan Sarovar Sanctuary, Kutch Bustard Sanctuary, Banni Grasslands Reserve andChari-Dhand Wetland Conservation Reserve etc..

[edit]Culture

[edit]Language

The languages spoken predominantly in Kachchh is Gujarati, Kachchhi and to lesser extent Sindhi, and Hindi. Script of Kachchhi language has become extinct and it is mainly written in the Gujarati script. Samples of Kachchhi script are available in Kachchh Museum. Increased use of Gujarati language is mainly because of being it a medium of instruction in schools. Often Kachchhi language is mistaken as dialect of Gujarati, however this is not true. Kachchhi language bears more grammatical similarity with Sindhi and words with Gujarati.

[edit]People

Kutch district is inhabited by various groups and communities. Many of these have reached this region after centuries of migration from neighbouring regions of Marwar (Western Rajasthan), Sindh,Afghanistan and further. Even today, one can find various nomadic, semi nomadic and artisan groups living in Kutch.Some communities came from Sind,(mostly Kutchi speaking-Lohanas,Bhatiyas,Khatris..)and some from Saurashtra.(Gujarati speaking-Sorathiya,Ahir,Girnara..)Many migrated from north Gujarat ,especially in Vagad region(Gujarati speaking- Prajapati)

The major groups such as the Lohana, Bhatia, Kapdi, Khumbar, Jadeja, Gadhvi, Darbar, Kathis,Rajputs, Mali Samaj, Leva Patel, Kadva Patel, Brahmins, Nagar Brahmins, Nandwana Brahmins,Khatris, Rabaris, Rajgor, Shah, Bhanushali, Jains (Visa and Dasa Oswal), Kutch Gurjar Kshatriyas,Mistris, Kharwa, Meghwals, Wankars, Vankaras, Ahirs, and many others have adopted a settled lifestyle and have struck a life rhythm close to that of modern-day towns. The Banni region is home to a number of nomadic Sindhi-speaking Muslim groups such as the Dhanetah Jaths, Halaypotra,Sanghar [Kutch Muslam Sanghaar Jamat-now in Karachi] Pakistan Hingora, Hingorja, Rahima,Bhadala, Mutwa, Raysipotra, Sammas, Theba and Node, maintain more traditional lifestyles.

[edit]Economy and Industries

| | This article may contain wording that merely promotes the subject without imparting verifiable information. Please remove or replace such wording, unless you can cite independent sources that support the characterization. |

Kutch is a growing economic and industrial hub in one of India's fastest growing states - Gujarat. Its location on the far western edge of India has resulted in the commissioning of two major ports Kandla and Mundra. These ports are near most to the Gulf and Europe by the sea route. The hinterland of north-western India hosts more than 50% of India's population. Quality of roads is good in Kutch. The large part of the growth of Kachchh came after tax relief provided by the government as part of 2001 earthquake relief.

Due to the existence of 2 major ports, transportation as a business has thrived. Since historical times the people of Kutch have formed the backbone of trade between Gujarat mainland and Sindh. After the formation of Pakistan this trade stopped for good, but due to the inception of the Kandla port, trade boomed again.

Kutch is Mineral rich region with very large reserve of Lignite,[3] Bauxite, Gypsum among other minerals. Kachchh got tax break for Industries for 15 years after the major earthquake on January 26, 2001. Lignite is mined only by Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation (GMDC) at its 2 mines in Panandhro and Mata-No-Madh. The Panandaro mines has now been reserved for GEB and GMDC power plants and GMDC has stopped supply to other industries from there.[4] This has adversely affected local trucking business.

Kutch also houses Sanghi Industries Ltd's Cement Plant. It is the India's single largest Cement Plant[citation needed]. The company is now planning to increase the capacity at its Abdasa location from 3–9 million tons per annum.[5] By 2015, the company plans to produce 20 million tons.[5] Kandla port is also in Kutch. It is considered Gateway to India's North. It is managed by the Kandla Port trust.

Other major Industries in Kutch are TATA POWER's first 4000 MW Ultra Mega Power Project(UMPP)of India. Adani Power expects to tie up funds for it's 3300 MW plant by March 2012 and is on track to complete the installation of 10,000 MW projects by 2013. The other major companies are the Welspun Group of Companies, Ajanta Clocks,Orpat , JayPee Cements, Jindal Steel and One of the largest windmill farms concentration. Kutch region is also a major producer of salt.

Kucth district has a scanty forest cover. Hence there is negligible risk of illegal cutting of forests. This coupled with the adequate facilities available at Kandla port has helped establish the timber market. In 1987, "Kandla Timber Association" was formed in order to resolve the specific, problems of Timber Importers and Timber allied industries coming up during the period. The Timber industry is growing at a faster pace with 300 saw mills working in Gandhidham-Kandla Complex.

The Little Rann of Kutch is known for its traditional salt production and various references mention this to be a 600 years old activity. During the British period, this activity increased manifold. It was used to fund a substantial part of the military expenses of the British government. Communities involved in salt production are mainly Chunvaliya Koli, Ahir and Miyana (Muslim), residing in 107 villages in the periphery of Lesser Rann of Kutch. These communities are traditionally known to have the skills of salt production and are known as 'Agariyas'. Water quality in 107 villages of Lesser Rann of Kutch is saline, thus agriculture is not an option .Hence salt production is the only livelihood option for Agariyas. As per the Salt Commission's report there are 45000 Agariyas working in the salt pans of Kutch. Out of the estimated total annual production of India of about 180 lakh tonnes, Gujarat contributes 75% - mainly from Kutch and other parts of Saurashtra.

Other Traditional industries in the areas include manufacture of Shawls, handicrafts, and silver items.

[edit]Handicrafts

Kachchh has a strong tradition of crafts.

The most famous craft of the region is its diverse embroideries. The finest aari embroidery was carried out for the royalty and wealthy families. Traditionally women in rural areas do the embroidery for their dowries.[6] Unfortunately many of these fine skills have now been lost, though some are being rejuvenated through handicrafts initiatives. In 1950, local social leader Dr. Manubhai Pandhi worked with local artists and the central government to help the dying handicraft. Today over 16 types of embroidery are being produced commercially by a few societies and a couple of private corporations. Some of the finest new embroidery in the world is being produced by over 6,000 women artisans of the region.

Some of the embroideries still being produced in the region are

- Kapdi (bava)

- Jadeja

- Gadhvi (Charan)

- Ahir

- Pakko

- Neran

- Kambira

- Khudi Teba

- Chicken

- Katri

- Chopat

- Gotan

- Mukko

- Soof

- Kharek

- Jat - Gracia

- Jat - Fakirani

- Noday

- Jat Daneta

Embroidery styles like Zardosi, Bhanusali, Jain, etc. are today extinct and one can see old pieces in museums or with collectors only.

Important resource centers for embroidery in the region are Shrujan, Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan (KMVS), Kalaraksha and Women Artisans' Marketing Agency (WAMA).

Another important art of Kutch is bandhani, which primarily originated in the region. Women wear saris of bandhani art on festive occasions like marriages or holidays like Navaratri and Diwali.

Kutch has a history of very fine quality Ajarakh printing. This is a very complex hand printing technique using wooden blocks and natural dyes. Similar techniques are seen in Bardmer in Rajasthan and Sind in Pakistan. The Ajarakh from each region has some subtle differences. Technically the Ajarakh printed today in Kutch is by far the finest of the lot. The printing is done by a lengthy process which can take up to a couple of months for the most complicates pieces. Ajarakh is being practised today in Dhamadka and Ajarakhpur villages in Kutch.

Mud work is another artwork of Kutch. Artistic wall pieces made with mud and mirror work are used to decorate homes.

Handmade, copper-plated cattle bells that are artistically calibrated to a note are made in the region. The bells have a very sweet and distinct sound that, although very soft, can travel very large distances in the open desert. These bells were traditionally put around cattle necks so that they could be easily located if they get lost. The bells are made by approximately 25 families in the villages of Zura, Nirona and Bhuj.

Kutch has many leather artisans who make products like shoes, sandals, mirrors, small pouches, etc. from leather. Traditionally hand tanned leather was used but has been almost replaced completely by leather imported from outside. The very high skilled artisans decorate the articles by doing embroidery or cutting various shaped windows in the leather. These artisans can be found in the villages like Sumarasar, Nirona, Zura, Bhirandiyara, Hodko, Khavda, etc. in and around the Banni region.

Lacquer work is carried out by the Vadha community. This group used hand-operated lathes to shape wood and decorate it with lacquer which is colored. The simple but highly skilled technique creates beautiful products which are a delight to see.

Kutch is home to a school of handloom weaving. The weavers weave wool, cotton and acrylic yarn to make products like shawls, yardage, jackets, etc. Bandhani (tie-dye) is carried out on the shawls in some cases. The biggest center for this is Bhujodi village near Bhuj.

[edit]Religion

As per the 2001 census, the district's population was 1,526,331, of which most around are Hindu. The remainder of the population adhere to mostly Jainism and Islam. There are also some Sikhs and a Gurudwara is also situated in kachchh at Lakhpat. This Gurudwara was originally a house where the first Guru Guru Nanak stayed during his journey to Mecca. The Swaminarayan Sampraday has a huge following in this region. Their main temple in this district is Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, Bhuj. Anjar city is the really famous also as Swaminarayan Mandir and Swaminarayanians. A related Sarswat Brahmin are called Kutchhi Sarswat Brahmin. Maheshwari (Maheshpanthi) Shampraday.

[edit]Food and drink

The majority of the population is vegetarian. Jains, Buldhmins and some other caste perform strict vegetarianism. Jains also refrain from eating kandmool food grown below the ground such as potatoes, garlic, onion, suran, etc. Hindus perform various degree of vegetarianism but certainly do not eat beef.

In the villages, staple foods include bajra and milk; bajara na rotla with curd and butter milk is very common food for all the Gujarati people. Bajra was introduced by a brave king of this region named Lakho Fulani. During his period of exile, he came to know about this grain in some tribal regions. They also extensively drink buttermilk during lunch. Milk is considered to be sacred food and offering it to somebody is considered a gesture of friendship and welcoming. Settlement of dispute invariably follows offering milk to each other as a concluding remark. In the Kutchi engagement ceremony, the bride's family offers milk to the groom's relatives as a symbol of accepting their relationship.

Tea is the most popular drink in this region and is enjoyed irrespective of sex, caste, religion or social status. Tea stalls where groups of people chat over tea are invariable sights of every village or town entrance from early morning to late evening. Most people drink it with milk and sugar. Offering black tea to guests is considered to be a bad gesture. Tea without milk is offered when people are visiting host to mourn death of relatives. Tea was introduced in this region by the British as part of medicinal purpose to counteract the plague epidemic in the early 19th century. Alcoholic liquor is another popular drink, though it has been illegal to drink or possess since Kutch was incorporated within Gujarat. Most of the liquor drunk in this region is distilled from molasses by local people in villages. As a rule, women do not drink alcohol.

[edit]History

Remote and sparsely populated while the district of Kutch may be, it has had an interesting history. The Indus valley civilization, known to be one of the first ever civilised societies consisted of the ancestors of Kutchis as well as others. However now most of the river lies in Pakistan after India was split up.

[edit]Prehistoric period

A few major towns of the Indus Valley Civilization are located in Kachchh. Dholavira, locally known as Kotada Timba, is one of the largest and most prominent archaeological site in India belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization. It is located on the Khadir island in the northern part of the Kachchh district - the island is surrounded by water in the monsoon season. The Dholarvira site is believed to have been inhabited between 2900 BCE and 1900 BCE, declining slowly after about 2100 BCE, briefly abandoned and then reoccupied, finally by villagers among its ruins, until about 1450. ZAARA no Yuddh is considerd to be one of the most fierce battle after Mahabharat was battled in Lakhpat taluka.

[edit]Medieval and British period

Kutch was formerly an independent kingdom, founded in the late 13th century by a Samma Rajput branch called Jadeja Rajputs. The Jadeja dynasty ruled not only Kutch but also much of neighboring Kathiawar for several centuries until the independence of India in 1947. In 1815 Kutch became a British protectorate and ultimately a princely state, whose local ruler acknowledged British sovereignty in return for local autonomy. Bhuj was the Capital of Princely State of Kutch. One surviving relic of the princely era is the beautiful Aina Mahal ("mirror palace"), built in the 1760s at Bhuj for the Maharao of Kutch by Ram Singh Malam who had learnt glass, enamel and tile work from the Dutch. Along with that during that time period Kutch had its own currency, while the rest of British India was using rupees. The Maharao also had built at his expense the Cutch State Railway.

[edit]Modern period

Upon the independence of India in 1947, Kachchh acceded unto the dominion of India and was constituted an independent commissionaire. It was created a state within the union of India in 1950. On June 1, 1948, Chhotalal Khovshaldan Desai became first Chief Commissioner of Kutch State. He was succeeded by Sambhajirao Appasaheb Ghatge in 1952. He was in office till October 31, 1956. On November 1, 1956, Kachchh State was merged with Bombay state, which in 1960 was divided into the new linguistic states of Gujarat and Maharashtra, with Kachchh becoming part of Gujarat state.

On the Partition of India in 1947, the province of Sindh, including the port of Karachi, became part of Pakistan. The Indian Government constructed a modern port at Kandla in Kutch to serve as a port for western India in lieu of Karachi. There was a dispute over the Kutch region with Pakistan and fighting broke out just months before the outbreak of the Second Kashmir War. Pakistan claimed 3,500 sq mi (9,100 km2) of the land and an international tribunal was set up. It awarded 350 sq mi (910 km2) of the claimed land to Pakistan, the rest remaining with India. Tensions flared again during the Atlantique Incident as it came just weeks after the 1999 Kargil Conflict.

The epicentre of the 2001 Gujarat Earthquake was in this district. It was the most severe of the more than 90 earthquakes that hit Kutch in 185 years. Much of Bhuj was destroyed or damaged, as were many villages. Many of the attractions of Bhuj, including the Aina Mahal, have still not been restored as of 2009.

[edit]Major Bollywood film shootings

J. P. Dutta's Bollywood film Refugee is shot on location in the Great Rann of Kutch and other locations in the Kutch district of Gujarat, India. This film is attributed to have been inspired by the famous story by Keki N. Daruwalla based around the Great Rann of Kutch titled "LOVE ACROSS THE SALT DESERT"[7] which is also included as one of the short stories in the School Standard XII syllabus English text book ofNCERT in India.[8] The film crew having traveled from Mumbai was based at the city of Bhuj and majority of the film shooting took place in various locations around in the Kutch District of the Indian state of Gujarat including the Great Rann of Kutch (also on BSF controlled "snow white" Rann within), Villages and Border Security Force (BSF) Posts in Banni grasslands and the Rann, Tera fort village, Lakhpat fort village, Khera fort village, a village in southern Kutch, some ancient temples of Kutch and with parts and a song filmed on set in Mumbai's Kamalistan Studio.

Just after the film shooting of Refugee finished, the film crew of another Bollywood film "Lagaan" descended on Bhuj in Kutch and shot the entire film in the region, employing local people and villagers from miles around. A set of a full period Village was constructed for the film with typical Kutch style mud houses or huts with thatched straw roofs called boongas.[9]

Kutchi people in other parts of the world : Trinidad and Tobago , Kenya, Tanzania, U.K and Guyana, Province of Sindh, Pakistan. Kuthci people proud to be Kutchi in Karachi and rest part of Sindh,

[edit]See also

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Kutch District |

- 2001 Gujarat earthquake

- Bhuj

- Gandhidham

- Harilal Upadhyay

- Khavda

- Nakhatrana

- Mandvi

- Rann of Kutch

- Banni grasslands

- Princely State of Cutch

[edit]References

- ^ [1]

- ^ Karanth, R. V.; Gadhavi, M. S. (2007-11-10). "Structural intricacies: Emergent thrusts and blind thrusts of central kachchh, western india".Current Science 93 (9): 1271–1280

- ^ The brown gold of Kutch - By tapping the huge mineral deposits of the Kutch region, Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation Ltd. plans to turn the backward area into a prosperous one.; SPECIAL FEATURE: GUJARAT; By V.K. CHAKRAVARTI; Volume 20 - Issue 06, March 15–28, 2003; Frontline Magazine; India's National Magazine from the publishers of THE HINDU

- ^ Steel Guru

- ^ a b "SIL to set up cement plant in Kutch" (cms). News article (Ahmedabad: Times of India). 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ^ Elson, Vickie (6 1979). Museum of Cultural History, University of California.

- ^ LOVE ACROSS THE SALT DESERT; by Keki N. Daruwalla. Pdf of full story posted at Boston University at [2]. Bollywood connection - J. P. Dutta's "Refugee" is said to be inspired by this story; learnhub, University of Dundee

- ^ (iii) Supplementary Reader; Selected Pieces of General English for Class XII; English General - Class XII; Curriculum and Syllabus for Classes XI & XII; NCERT. Also posted at [3] / [4], [5]

- ^ Google Books Preview: "The spirit of Lagaan - The extraordinary story of the creators of a classic"; by Satyajit Bhatkal; Published by Popular Prakshan Pvt. Ltd.; ISBN 81-7991-003-2 (3749)

- The Great Run of Kutch; Dec 10, 2006; The Indian Express Newspaper

- Hotel Prince - Hotel in Kutch

[edit]External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gandhidham

| | This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. The talk page may contain suggestions. (September 2010) |

| Gandhidham | |

| — city — | |

| | |

| Coordinates | 23.08°N 70.13°ECoordinates: 23.08°N 70.13°E |

| Country | India |

| State | Gujarat |

| District(s) | Kachchh |

| President | Meenaben A Bhanusali |

| Municipality | Gandhidham Municipality |

| Population | 166,388 (2001) |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

| Area | • 27 metres (89 ft) |

Gandhidham (Gujarati: ગાંધીધામ, Sindhi: گانڌيِ ڌام) is a city and a municipality in the Kachchh District of Gujarat state of India. The town was created in the early 1950s for the resettlement of the refugees from Sindh of Pakistan in the aftermath of the partition of India. In recent history Gandhidham is a fast developing city in Gujarat state.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]History

Soon after the separation of Pakistan from India in 1947, a large group of refugees from Sindhof Pakistan came to India. Maharaja of Kutch His Highness Maharao Shri Vijayrajji Khengarji Jadeja on advice of Gandhiji, gave 15,000 acres (61 km2) of land to Bhai Pratab, who founded Sindhu Resettlement Corporation to rehabilitate Sindhi Hindus uprooted from their motherland.[1] Sindhi Resettlement Corporation was formed ( fondly called SRC)withAcharaya Kriplani as chairman and Bhai Pratap Dialdas as managing director. Main objective of the corporation was to assist in the rehousing of displaced persons by the construction of new town on a site few miles inland from location selected by Government of India for new port of Kandla on the Gulf of Kachchh. The first plan was prepared by a team of planners headed by Dr. O. H. Koenigsberger, director of the division of housing in Government of India. Subsequently plan was revised by Adams Howard and Greeley company in 1952. The foundation stone of town was laid with blessings of Mahatama Gandhi and hence town was named Gandhidham.